|

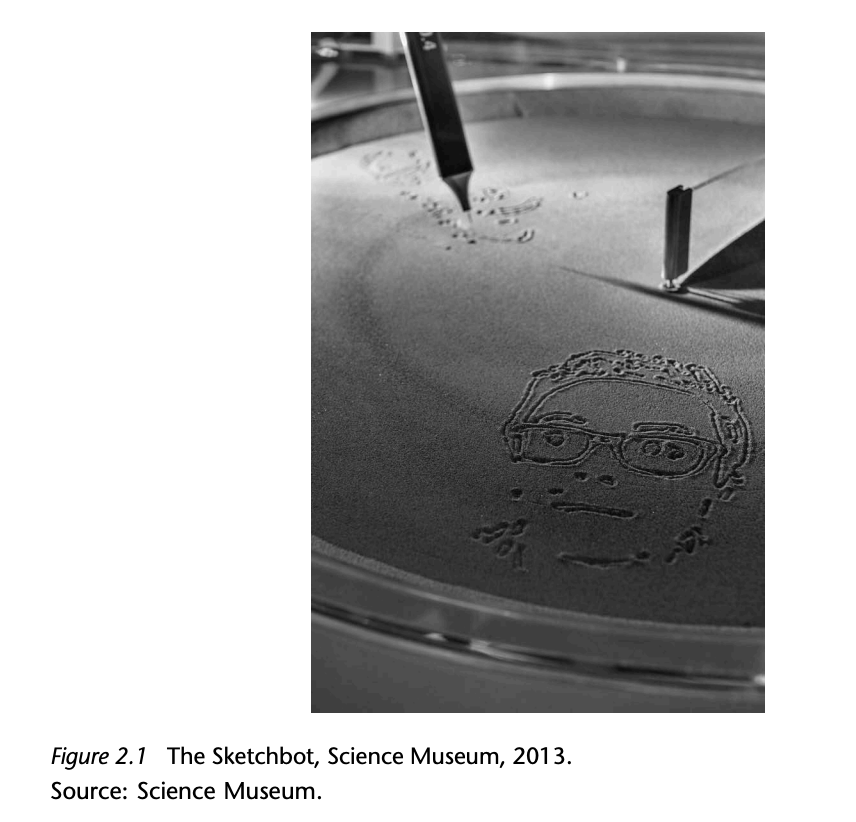

David Patten is Head of New Media at the Science Museum, London, where his role includes managing all aspects of new media from conceptual design, prototyping and production to project managing external developers and production companies. He has a background in electronics and computer science, and has worked at the Science Museum for over 30 years, developing exhibitions and leading development teams including the technical systems for the Science Museum’s Wellcome Wing and Dana Centre, which opened in 2000 and 2004 respectively. Recent work includes Web Lab, the multi-award-winning collaboration with Google and Engineering Your Future, an interactive exhibition for teenagers on engineering Interview with Dave Patten David Patten, Dirk vom Lehn and Wally SmithIf we are developing a permanent gallery focused on our core collection, it will be in the museum for 20 to 25 years. So ultimately what we want is for people to engage with the collection. Visitors can see real objects and participate in the story about them. So in this show that uses a lot of our collections, we're reducing the amount of technology we're putting in because technology isn't sustainable for such a long period of time. It is easy to maintain, with a few exception technologies that most of them will not last 25 years or so. What works is a technique that uses time-based media (video and audio). This technology makes it fairly easy to switch to new formats and update playback hardware. However, anything you create programmatically is much more difficult. Software and hardware change over time and cannot be replaced with similar ones. Because of these difficulties, we are reducing skills related to computing and programming in our permanent exhibition display. Years ago, I installed the first tracker ball in a museum and people didn't know what to do with it. This was in the late 1980s and before Windows 3. At the time, most people had no experience with Apple Macintosh computers, and Microsoft did not have a mouse-based graphical user interface at the time. It took a few minutes for people to connect this ball moving with the items moving on the screen. We've experimented with this kind of interface for a while, but haven't installed Trackerball for quite some time as our visitors struggled with it. Within a year of Microsoft releasing Windows 3, things changed. People have fully understood the use of tracker balls (essentially upside down mice). Because tracker balls have been exposed to tracker balls everywhere outside of the museum. Another example of this is the touch screen. Touch screens have always been a fairly intuitive way to interact with computers. When we first introduced touch screens to museums, there was a big problem. We had a lot of video screens in the museum to play David Patten and the like. 24 static video. When people started seeing touch screens, they assumed that all screens were touch screens. We haven't always mounted our video screens very effectively. In fact, we used to place video screens on shelves, in openings. Museums now have a lot of 'point and click' touch screens. Within a few years of the iPhone's release, people's behavior had changed again and they expected all screens to be gesture-based. Then they try and swipe the old touchscreen but it doesn't work. The visitor then asks if the exhibit is out of order or if they are doing something wrong. Ultimately, this is a problem for us. What museums don't want is to make visitors feel stupid. The visitor is always right. Visitors can take control of their experience and take in a story or information at their own pace, or try different things and see different results. If you're dealing with something like big data, quantum computing, or nanotechnology, you're taking people to a very different world and a very different experience. You can tell, but objects don't really tell a story. Ultimately, technology is expensive to acquire and maintain. This technology had to really prove its true value to the museum by providing a great visitor experience, and we decided to incorporate it into our exhibition. Sketchbot takes a picture of your face using your webcam via Canvas in HTML5 and processes it into line art. This data is then sent to a robotic arm and it starts sketching the face into a sand pit. Check out the video below where the sketchbot draws my face in the sand. This was my favorite experiment in the Web Lab. I personally would like to see a lot fewer screens in museums. That doesn't mean there won't be a lot of digital interactivity, but I don't think inputs or outputs need to be displayed on screen all the time. Some of the best inputs and outputs don't show up on screen. Sketchbots were great but needed a lot of care. They are mechanical devices and require a team of competent and confident people to maintain them. Because some of these services were cloud-based, managing the space between software and physical was complex. It's gotten easier since then, but those things can still be expensive. A good exhibition tells a story. It can't be a nice object selection with some panel display and that's all you need. I think digital technology is still relatively new to museums. I've been working in the field for 30 years, but museums have been around for hundreds of years. We've been writing label captions for hundreds of years. You could argue, we're not really good at it or it's really hard to write good label captions. Larger museums like ours are taking notice of the opportunities VR offers. But I think we're all definitely moving toward augmented and mixed reality, which allows us to do all sorts of really interesting things for museum goers in a much less intrusive way. In the future, these experiences will be achieved using some sort of lightweight wearable device. These technologies allow you to slice an object in front of your visitors' eyes to show them what's inside and how it works. A context can be created around the object. All of these technologies are available in many ways now and will only get easier to use. One of the biggest challenges for museums is having the resources to create enough content to do this. It is often difficult to find time to go back and reinterpret old exhibitions and galleries. We have a digital record of our museum collections, which has grown over quite a long time. The quality of that data is often inconsistent. It depends on when and who put it. For a museum, it may take years of curatorial work to go back and clean up all the data before they can use it to create something new. I think it's appropriate for both of us to do that, because we believe that what makes a museum unique is its collection. Every museum went through a period 15 or 20 years ago when there was tremendous internal debate about the impact of building websites and publishing collections online on visitor numbers. Some argued that no one would come to the museum anymore. That was blatantly untrue. Rather, websites that post collections drive people to museums because they see them online and want to come and see them in person. It's exciting to be so close to real artifacts. To stand next to Stevenson's rocket. Standing next to the first airplane to cross the Atlantic Ocean. It's a special kind of tangible experience that you just can't get the same way you see it online, although high-quality VR and MR systems can ultimately change that. Additionally, museums are inherently social experiences. When a museum seeks to personalize a visit, I'm interested in how you can try to keep the serendipity and surprise there. How can we avoid the fact that personalized visits can lose some of their social aspects and still allow for a shared experience? One of the joys of museums is that when you go with other people, you spend a lot, if not most, of your time talking to the people you're with. With any new technology, we must constantly think about not only what it can do, but what it can change about the museum experience that is so dear to us. We just scanned Stephenson's rocket with LiDar and photogrammetry. It took 11.5 hours and it was just one object. It consisted of a series of LiDar scans and approximately 2,500 photos. Not only did it take 11.5 hours to capture, it took weeks to capture. Process the results and get the model. This is not possible for all objects (or a significant number of objects) if the collection is large. For us, it's important that VR technology makes visitors want to see the objects that were at the center of creating the VR experience. We did an audience study in this regard, with very positive results suggesting that VR experiences can actually lead people to look more closely at (real) objects. However, VR is quite expensive to create and maintain on the museum floor as headsets are still expensive and fragile. We need staff to gain experience. As such, it is not something that can be widely adopted by current museums. But if you had a special exhibition with one object you really wanted, you would have wanted to bring it to life in a different way. I also started thinking about what it means to tell stories in an immersive environment in an effective way. We're really interested in all forms of immersive environments, from large room projections with lots of people to mixed and virtual reality. When you actually tell a story in such an environment, you, the participant, become the director of the story. Storytelling and consumption are really different. We have nearly 3.5 million people each year and they come from very different backgrounds. Some people expect the latest science. Whether physical or digital interactions, some people expect to be able to interact with things. Some people come because they want to see our collection of art or to see a particular object. People come with all kinds of different reasons and motives. We are a big museum and we need to try to satisfy them all. The question of deploying new technology is interesting. We tend not to focus too much on it, in part because we've done it in the past and it's really challenging. We're not using really new technology. Because museums aren't set up to do that. The investment is high and the failure rate is high. Instead, we are bringing technology into the museum context that people have never experienced in a museum before. After all, museums have to present what people want and enjoy, and don't want to create a bunch of things that don't work. So be careful how you use it We also visit the big trade shows to see what the latest tools are coming out. What will we see in 2-3 years? From different museums to the streets, we are constantly looking for inspiration in all kinds of places. Sometimes it's about new technology, sometimes it's about looking at technology in a very different way. But I think museums are an act of constant mixing and balancing to provide a myriad and relevant experiences for a diverse audience. The rise of Translate makes it clear that people will use their personal devices to automatically translate texts and that the museum experience will become a more positive one for international visitors. We can also see the emergence of various technologies for people with disabilities. Right now we're doing a lot of closed captioning for video and sign language, but I think in the future more and more people will be using portable devices to do all of that. It will change what we do in museums. But I think there's also a little inherent risk that anyone can do something with a cell phone in a museum and it might not necessarily be us. So, should we know what other people are doing if we don't? Should we be concerned about it? We conducted the first study on mobile phone use in museums in 2012 and the second in 2015. Rather, internet usage within the museum has declined slightly. The reason for this decline in internet use is that compared to 2012, almost everyone now has a smartphone. I don't think there is yet a killer application for mobile devices that works across museums. And building apps is very expensive and very difficult to market. We've built some really successful apps. It downloads well not only in the UK, but also in the US, Russia, China, India and South America. Like some gaming apps, these successful apps tend to be free, so in effect the exhibit sponsors pay for them. We're not making money with these apps, but they're worth the money because we use them to share the museum experience and the museum brand. Museums are amazingly creative places. We have more stories than you can imagine. I love being a part of it and helping to create and tell that story to visitors. But I also love that the people who work at the museum are really passionate and really interesting people from different backgrounds. Every project we work on at the museum involves working with a diverse mix of people. The pace of change continues to accelerate, and you are always running, and it's just thrilling! With technology, change is happening fast. For example, we believe that we are just at the beginning of the development of personal devices. Sooner or later we'll see really lightweight wearables and some kind of glass/headset devices. Perhaps within the next five years. When these kinds of devices become commonplace, their ability to transform museums is enormous. It's really interesting and can ultimately mean you can hide all your skills.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Myungja Anna KohArtist Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed