A Note: Formative and Summative Assessment in the Classroom (Dixson)Two tools teachers commonly use to assess student learning of new material and knowledge of state standards are formative and summative assessments.

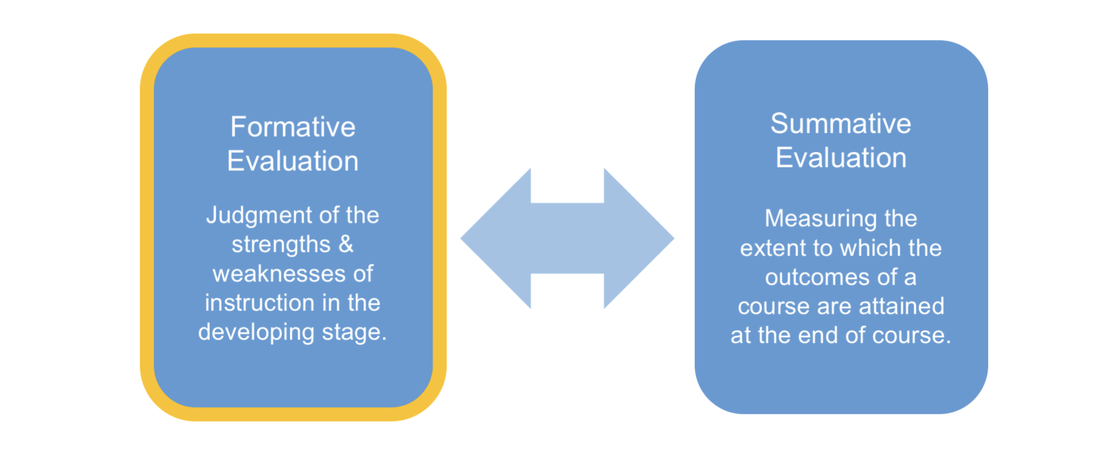

Formative assessments involve collecting data to improve student learning, while summative assessments use data to assess how much students know or have at the end of the learning process (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and U.S. Measurement Committee). School-wide formative assessment, a precursor to formal assessment, has led to an increased reliance on assessments among teachers in general. This increased use of formative assessments has led test publishers to develop and validate formative assessments that are based on national samples and produce scores that are more psychometrically robust than those typically developed and used by teachers. Formative Assessment Wiggins (1998) asserted that “the purpose of [formative] assessment is primarily to educate and improve, rather than simply audit, student performance” (p. 7). Formative assessment has been defined as “self-assessment activities by teachers and students that provide information to be used as feedback to modify teaching and learning activities” (Black & Wiliam, 2010, p. 82). Formative assessment comes in two main forms: spontaneous assessment and planned assessment (Cook, 2009). Voluntary formative assessment occurs when (a) in class, the teacher reads misunderstandings in students' body language and asks students about their understanding; (b) when the teacher asks students to provide examples of It is done spontaneously together. Summative Assessments Summative assessments are “cumulative assessments that attempt to capture what a student has learned or the quality of his or her learning and to judge performance against some standards” (National Research Council, p. 25). Unlike formative assessments, which are typically used to provide feedback to students and teachers, summative assessments are typically high-stakes assessments and are used to obtain a final assessment of how much learning has occurred, i.e., how much the student knows (Gardner , 2010). Summative assessments are almost always graded, are generally less frequent, and occur at the end of a lesson. Examples of summative assessments include final exams, state exams, college admissions tests (e.g. GRE, SAT, LSAT), final performances, and semester papers. Formative assessments should be used during class to help students learn the material both initially and throughout the learning process. Summative assessments can be used to assess how much learning students have gained and retained at the end of a unit, chapter, quarter, or semester. Additionally, sometimes it may make sense to use formative assessments summatively or summative assessments formatively, depending on the use of the assessment results (National Research Council, 2001). For example, a teacher may give the class a test (usually a summative assessment) to assess topics that need to be covered or retaught, rather than calculating a final grade. In summary, all assessments of understanding to feedback are formative (assessment of learning) and all assessments used to assess a student's knowledge at a specific point in time are summative (assessment of learning; Gardner, 2010).

0 Comments

A Note: What Do They Know? The six steps of successful theatre class assessment (Green)Designing thoughtful assessments that focus on key learning objectives can not only provide accountability and let students know what they've learned, but can also help you become a more effective teacher.

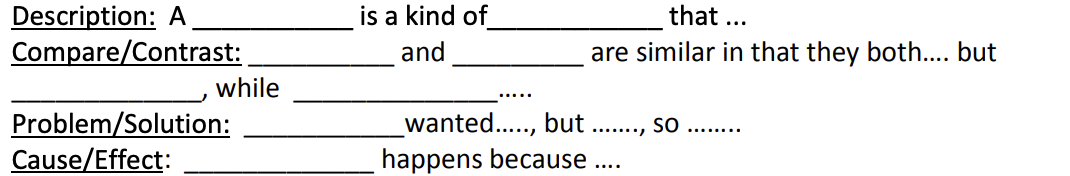

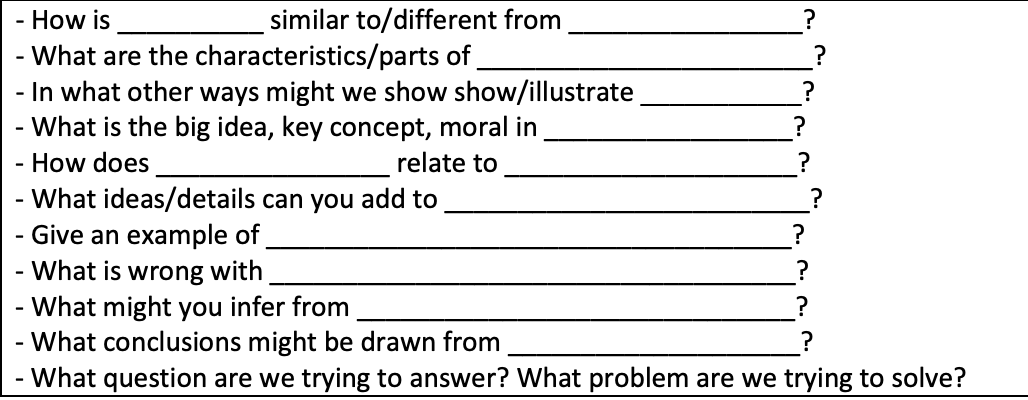

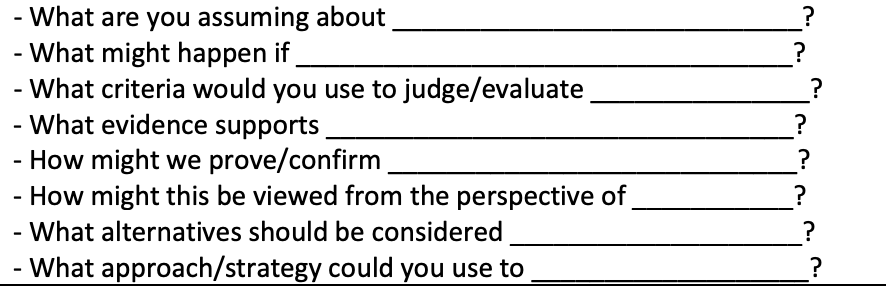

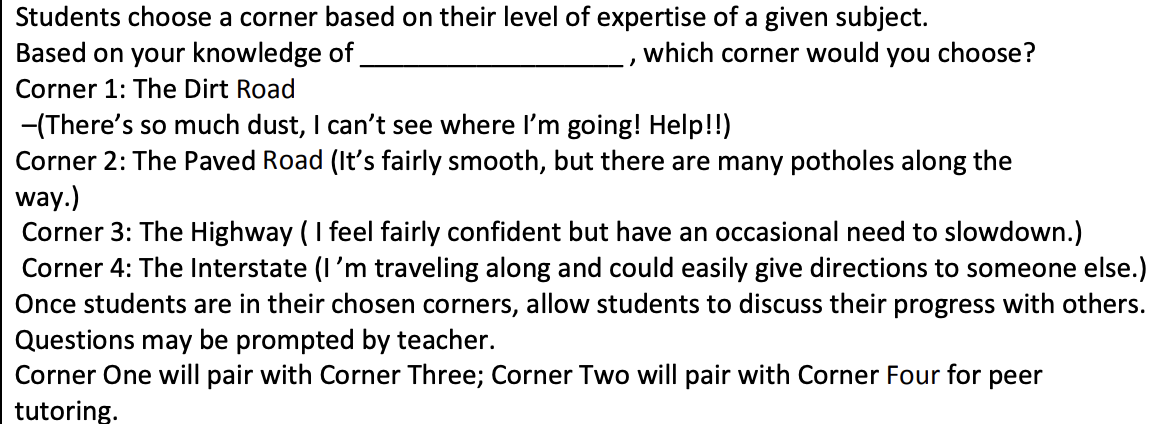

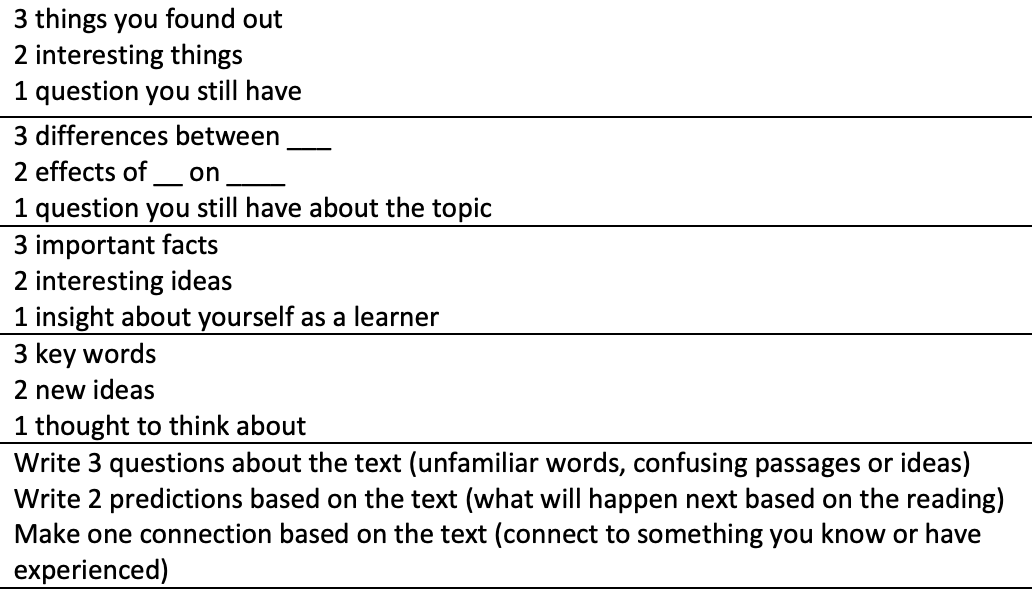

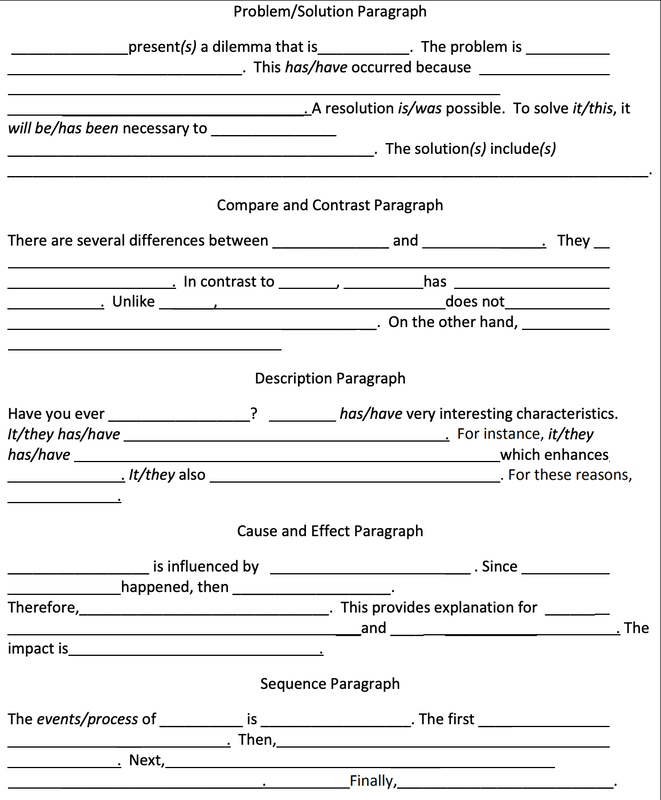

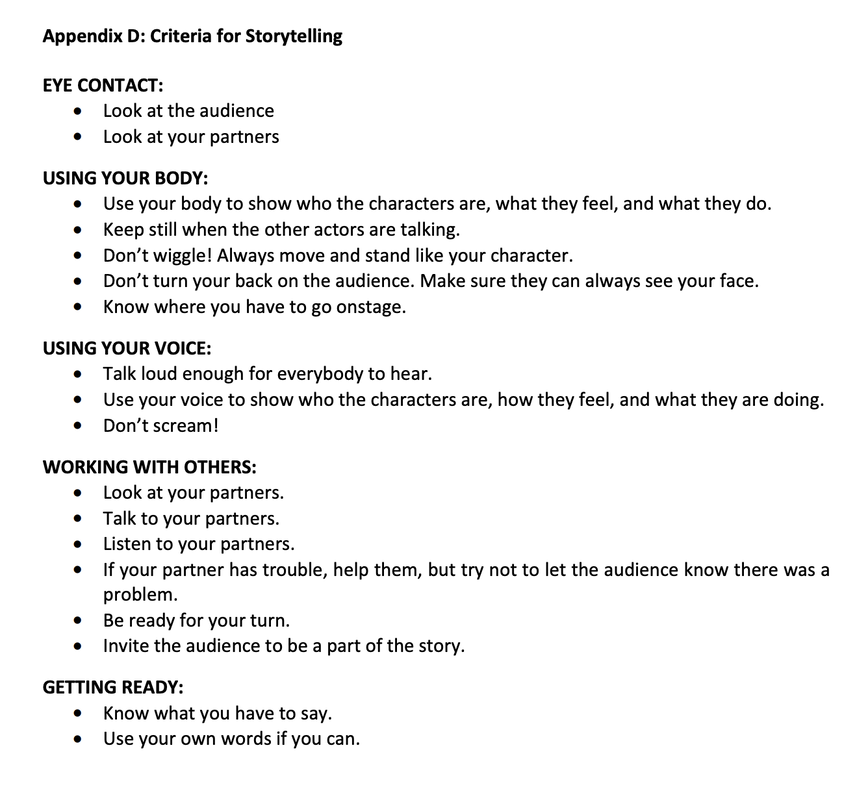

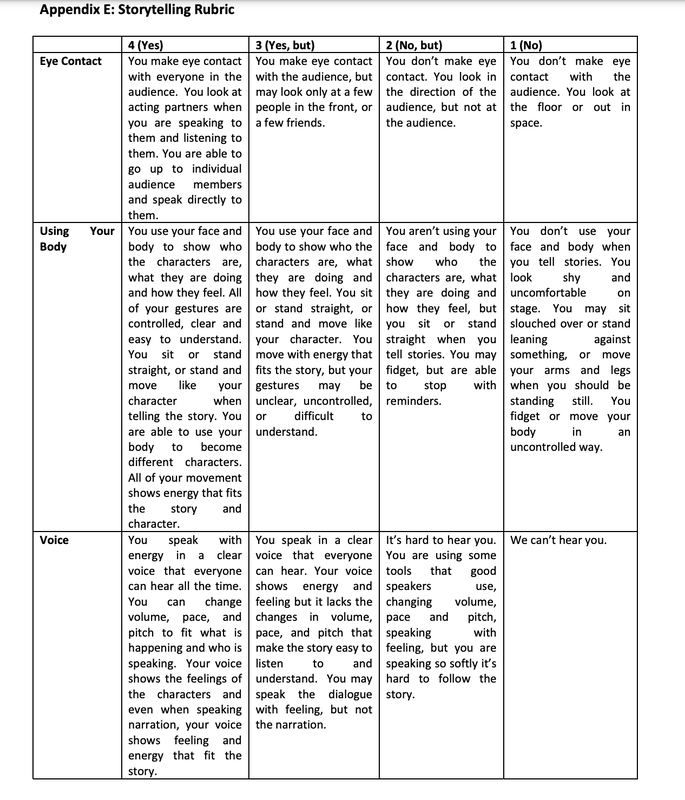

To this end, we have created six sequential steps that provide priorities and guidance for developing effective theater assessments, along with examples to help explain and demonstrate the approach. 1. Start with the end in mind. We borrowed the first step from Stephen Covey, who wrote the popular self-help book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. A more effective strategy is to plan this exercise by introducing lessons about pantomime, space use, and movement to create a feeling or story that builds on these key learning outcomes. “Who do you think is the most important person in this staged picture and why?” “Who is in the weakest position on stage and why?” “Who is the least important person and why?” By having students discuss and demonstrate their understanding of these body positions on stage, you can introduce the concept of strong and weak stage positions while assessing their understanding of the concepts as they contribute to the discussion. Depending on the clarity of your answers, you can review and re-teach or move on. These practical demonstrations can be great teaching and learning tools to spark discussion, connect activities to assessments, and apply these instructional concepts to the classroom. 2. Create a pre-assessment When a new year begins or a new unit begins, you will always want to check what theater skills your students already have. Have each student partner with someone they don't know well. Ask to find out your partner's name, age, and two unusual facts about him or her. Then ask your partner to describe three things they know about acting. Finally, have each student take a turn standing up and recalling seven things about their partner. This activity serves as an ice breaker to demonstrate the student's ability to memorize information, vocal skills (pronunciation, vocal variety, volume, breathing support), and comfort level with performance. Any pre-assessment should also be mindful of what skills you are building in your students. 3. Create a scoring guide to assess proficiency Grading guides or rubrics aren't just useful for paper/pencil tests. Using well-designed rubrics can not only improve your teaching content but also provide a more objective structure to your assessments. Creating specific grading criteria tailored to your learning objectives can easily be applied to theater performance tasks. This is a useful tool for both you and your students. One way to decide on a rubric is to first present it in question form. 4. In-class evaluation Some teachers believe that assessments should only be used at the end of a unit (so-called summative assessments). However, we believe that “checking things out as we go” also provides valuable information. Formative evaluation is an evaluation of learning that occurs during class, while summative evaluation is an evaluation of learning that occurs after class completion. Formative assessments can be powerful. Recent research has demonstrated that continuous assessment can be as effective as intensive educational interventions, such as one-on-one tutoring, in promoting student growth. As students learn what is evaluated in rehearsal, they become more aware of what makes a good performance. Finally, the final important step in formative assessment is providing students with the opportunity to apply feedback to achieve their goals. 5. Teach students to engage in peer and self-assessment. As instructors, we want our students to be able to function independently when they leave school and are no longer under guidance. In our experience, developing the ability to evaluate oneself is one of the ultimate goals of education. This teaches students to look beyond their own perspectives and see themselves in relation to the standards. It also teaches empowerment. When students eventually understand and internalize the standards, they will no longer rely on teachers to suggest corrections or pass judgment on their work. 6. Evaluate yourself. In the book The Drama Classroom: Action, Reflection, Transformation, Philip Taylor makes a powerful case for reflective theater practice. Willingness to modify teaching methods, open-mindedness, and flexibility are all characteristics that he suggests can improve teacher practice. Teacher self-assessment is something every educator should do. If all or some of your students seem to be struggling through self-assessment, you should definitely consider adjusting your teaching style. Tools for Formative Assessment /Techniques to Check for Understanding /Processing Activities11/25/2023 Tools for Formative Assessment /Techniques to Check for Understanding /Processing Activities by Compiled by K Lambert, OCPS Curriculum Services, 4/2012 1. Index Card Summaries/ Questions Periodically, distribute index cards and ask students to write on both sides, with these instructions: (Side 1) Based on our study of (unit topic), list a big idea that you understand and word it as a summary statement. (Side 2) Identify something about (unit topic) that you do not yet fully understand and word it as a statement or question. 2. Hand Signals Ask students to display a designated hand signal to indicate their understanding of a specific concept, principal, or process: - I understand____________ and can explain it (e.g., thumbs up). - I do not yet understand ____________ (e.g., thumbs down). - I’m not completely sure about ____________ (e.g., wave hand). 3. One Minute Essay A one-minute essay question (or one-minute question) is a focused question with a specific goal that can, in fact, be answered within a minute or two. 4. Analogy Prompt Present students with an analogy prompt: (A designated concept, principle, or process) is like _________________ because _________________________________________________. 5. Web or Concept Map Any of several forms of graphical organizers which allow learners to perceive relationships between concepts through diagramming key words representing those concepts. http://www.graphic.org/concept.html 6. Misconception Check Present students with common or predictable misconceptions about a designated concept, principle, or process. Ask them whether they agree or disagree and explain why. The misconception check can also be presented in the form of a multiple-choice or true-false quiz. 7. Student Conference One on one conversation with students to check their level of understanding. 8. 3-Minute Pause The Three-Minute Pause provides a chance for students to stop, reflect on the concepts and ideas that have just been introduced, make connections to prior knowledge or experience, and seek clarification. 9. Observation Walk around the classroom and observe students as they work to check for learning. Strategies include: 10. Self-Assessment A process in which students collect information about their own learning, analyze what it reveals about their progress toward the intended learning goals and plan the next steps in their learning. 11. Exit Card Exit cards are written student responses to questions posed at the end of a class or learning activity or at the end of a day. 12. Portfolio Check Check the progress of a student’s portfolio. A portfolio is a purposeful collection of significant work, carefully selected, dated and presented to tell the story of a student’s achievement or growth in well-defined areas of performance, such as reading, writing, math, etc. A portfolio usually includes personal reflections where the student explains why each piece was chosen and what it shows about his/her growing skills and abilities. 13. Quiz Quizzes assess students for factual information, concepts and discrete skill. There is usually a single best answer. 14. Journal Entry Students record in a journal their understanding of the topic, concept or lesson taught. The teacher reviews the entry to see if the student has gained an understanding of the topic, lesson or concept that was taught. 15. Choral Response In response t o a cue, all students respond verbally at the same time. The response can be either to answer a question or to repeat something the teacher has said. 16. A-B-C Summaries Each student in the class is assigned a different letter of the alphabet and they must select a word starting with that letter that is related to the topic being studied. 17. Debriefing A form of reflection immediately following an activity. 18. Idea Spinner The teacher creates a spinner marked into 4 quadrants and labeled “Predict, Explain, Summarize, Evaluate.” 19. Inside-Outside Circle Inside and outside circles of students face each other. Within each pair of facing students, students quiz each other with questions they have written. Outside circle moves to create new pairs. Repeat. 20. Reader’s Theater From an assigned text have students create a script and perform it. 21. One Sentence Summary Students are asked to write a summary sentence that answers the “who, what where, when, why, how” questions about the topic. 22. Summary Frames 23. One Word Summary Select (or invent) one word which best summarizes a topic. 24. Think-Pair- Share/ Turn to Your Partner Teacher gives direction to students. Students formulate individual response, and then turn to a partner to share their answers. Teacher calls on several random pairs to share their answers with the class. 25. Think-Write-Pair Share Students think individually, write their thinking, pair and discuss with partner, then share with the class. 26. Talk a Mile a Minute Partner up – giver and receiver͙ Kind of like “Password” or “Pyramid.” Both know the category, but the receiver has his back to the board/screen. 27. Oral Questioning 28. Tic-Tac-Toe/ Think-Tac-Toe A collection of activities from which students can choose to do to demonstrate their understanding. It is presented in the form of a nine square grid similar to a tic-tac-toe board and students may be expected to complete from one to “three in a row”. The activities vary in content, process, and product and can be tailored to address DOK levels. 29. Four Corners 30. Muddiest (or Clearest) Point This is a variation on the one-minute paper, though you may wish to give students a slightly longer time period to answer the question. Here you ask (at the end of a class period, or at a natural break in the presentation), "What was the "muddiest point" in today's lecture?" or, perhaps, you might be more specific, asking, for example: "What (if anything) do you find unclear about the concept of 'personal identity' ('inertia', 'natural selection', etc.)?". 31. 3-2-1 32. Cubing Display 6 questions from the lesson Have students in groups of 4. Each group has 1 die. Each student rolls the die and answers the question with the corresponding number. 33. Quick Write The strategy asks learners to respond in 2–10 minutes to an open-ended question or prompt posed by the teacher before, during, or after reading. 34. Directed Paraphrasing Students summarize in well-chosen (own) words a key idea presented during the class period or the one just past. 35. RSQC2 In two minutes, students recall and list in rank order the most important ideas from a previous day's class; in two more minutes, they summarize those points in a single sentence, then write one major question they want answered, then identify a thread or theme to connect this material to the course's major goal. 36. Writing Frames 37. Decisions, Decisions (Philosophical Chairs) Given a prompt, class goes to the side that corresponds to their opinion on the topic, side share out reasoning, and students are allowed to change sides after discussion 38. Somebody Wanted But So Students respond to narrative text with structured story grammar either orally, pictorially, or in writing. (Character(s)/Event/Problem/Solution) 39. Likert Scale Provide 3-5 statements that aren’t clearly true or false, but are somewhat debatable. The purpose is to help students reflect on a text and engage in discussion with their peers afterwards. These scales focus on generalizations about characters, themes, conflicts, or symbolism. There are no clear cut answers in the book. They help students to analyze, synthesize and evaluate information) 40. I Have the Question, Who Has the Answer? The teacher makes two sets of cards. One set contains questions related to the unit of study. The second set contains the answers to the questions. Distribute the answer cards to the students and either you or a student will read the question cards to the class. All students check their answer cards to see if they have the correct answer. A variation is to make cards into a chain activity: The student chosen to begin the chain will read the given card aloud and then wait for the next participant to read the only card that would correctly follow the progression. Play continues until all of the cards are read and the initial student is ready to read his card for the second time. 41. Whip Around The teacher poses a question or a task. Students then individually respond on a scrap piece of paper listing at least 3 thoughts/responses/statements. When they have done so, students stand up. The teacher then randomly calls on a student to share one of his or her ideas from the paper. Students check off any items that are said by another student and sit down when all of their ideas have been shared with the group, whether or not they were the one to share them. The teacher continues to call on students until they are all seated. As the teacher listens to the ideas or information shared by the students, he or she can determine if there is a general level of understanding or if there are gaps in students’ thinking.” 42. Word Sort Given a set of vocabulary terms, students sort in to given categories or create their own categories for sorting 43. Triangular Prism (Red, Yellow, Green) Students give feedback to teacher by displaying the color that corresponds to their level of understanding 44. Take and Pass Cooperative group activity used to share or collect information from each member of the group; students write a response, then pass to the right, add their response to next paper, continue until they get their paper back, then group debriefs. 45. Student Data Notebooks A tool for students to track their learning: Where am I going? Where am I now? How will I get there? 46. Slap It Students are divided into two teams to identify correct answers to questions given by the teacher. Students use a fly swatter to slap the correct response posted on the wall. 47. Say Something Students take turns leading discussions in a cooperative group on sections of a reading or video 48. Flag It Students use this strategy to help them remember information that is important to them. 49. Fill In Your Thoughts Written check for understanding strategy where students fill the blank. (Another term for rate of change is ____ or ____.) 50. Circle, Triangle, Square Something that is still going around in your head (Triangle) Something pointed that stood out in your mind (Square) Something that “Squared” or agreed with your thinking. 51. ABCD Whisper Students should get in groups of four where one student is A, the next is B, etc. Each student will be asked to reflect on a concept and draw a visual of his/her interpretation. Then they will share their answer with each other in a zigzag pattern within their group. 52. Onion Ring Students form an inner and outer circle facing a partner. The teacher asks a question and the students are given time to respond to their partner. Next, the inner circle rotates one person to the left. The teacher asks another question and the cycle repeats itself. 53. ReQuest/ Reciprocal Questioning ReQuest, or reciprocal questioning, gives the teacher and students opportunities to ask each other their own questions following the reading of a selection. The ReQuest strategy can be used with most novels or expository material. It is important that the strategy be modeled by the teacher using each genre. A portion of the text is read silently by both the teacher and the students. The students may leave their books open, but the teacher's text is closed. Students then are encouraged to ask the teacher and other students questions about what has been read. The teacher makes every attempt to help students get answers to their questions. The roles then become reversed. The students close their books, and the teacher asks the students information about the material. This procedure continues until the students have enough information to predict logically what is contained in the remainder of the selection. The students then are assigned to complete the reading 54. K-W-L & KWL+ Students respond as whole group, small group, or individually to a topic as to “What they already Know, what they want to learn, what they have learned”. PLUS (+) asks students to organize their new learnings using a concept map or graphic organizer that reflects the key information. Then, each student writes a summary paragraph about what they have learned. 55. Choral Reading Students mark the text to identify a particular concept and chime in, reading the marked text aloud in unison 56. Socratic Seminar Students ask questions of one another about an essential question, topic, or selected text. The questions initiate a conversation that continues with a series of responses and additional questions. 57. Newspaper Headline Create a newspaper headline that may have been written for the topic we are studying. Capture the main idea of the event. 58. Numbered Heads Together Students sit in groups and each group member is given a number. The teacher poses a problem and all four students discuss. The teacher calls a number and that student is responsible for sharing for the group. 59. Gallery Walk After teams have generated ideas on a topic using a piece of chart paper, they appoint a “docent” to stay with their work. Teams rotate around examining other team’s ideas and ask questions of the docent. Teams then meet together to discuss and add to their information so the docent also can learn from other teams. 6.Graffiti – Groups receive a large piece of paper and felt pens of different colors. Students generate ideas in the form of graffiti. Groups can move to other papers and discuss/add to the ideas. 60. One Question and One Comment Students are assigned a chapter or passage to read and create one question and one comment generated from the reading. In class, students will meet in either small or whole class groups for discussion. Each student shares at least one comment or question. As the discussion moves student by student around the room, the next person can answer a previous question posed by another student, respond to a comment, or share their own comments and questions. As the activity builds around the room, the conversation becomes in-depth with opportunity for all students to learn new perspectives on the text. A note: Formative Assessment in Theatre Education: An Application to Practiceby Chen, F., Andrade, H., Hefferen, J., & Palma, M. Arts educators tend to have two opinions on evaluation: Either they believe, often correctly, that they are continually evaluating student learning as a natural part of their practice, or they believe that the important outcomes of their teaching defy systematic assessment (Colwell 2004). Some educators argue that rubrics can actually ‘hurt kids,’ replace professional decision making by attempting to standardize creative processes (Wilson 2006), and undermine learning by focusing only on the most quantifiable and least important qualities of student work (Kohn, 2006). In fact, research on writing has shown that rubrics that emphasize qualities of writing typically considered to be highly subjective and difficult to teach, such as ideas and voice, are associated with meaningful improvements in students’ handling of those qualities in their writing (Andrade, Du and Mycek 2010; Andrade, Du and Wang 2008). Student participation in the assessment process, with or without a rubric, is a key component of assessment for learning (Stiggins 2006), or formative assessment.

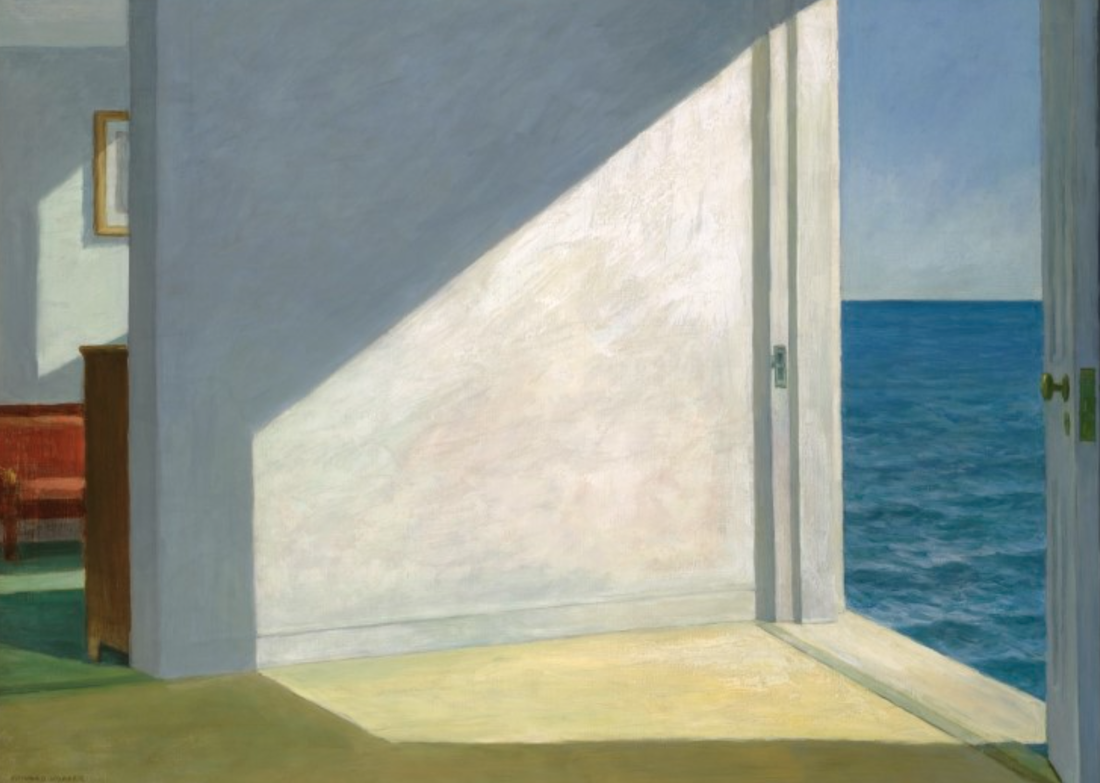

A key element of formative assessment is feedback to teachers and students, both formal and informal, about how much and how well students have learned. Research has shown that well-implemented formative assessment can effectively double a student's rate of learning (Wiliam 2007/2008).The heart of theater is the rehearsal process, where actors receive feedback on their performances and It is a continuous, formative assessment experience where you revise accordingly. Our work with theater professionals participating in a project called Artful Learning Communities: Assessing Arts Learning (ALC) strongly suggests that the results of formative assessments in theater education are similar to those reported in the studies cited above. The goals of the project are to: 1) Strengthen the capacity of elementary and middle school arts professionals to assess standards-based learning in the arts; 2) Promote improved student arts achievement through ongoing classroom assessment. 3) Develop the capacity of professionals to define, systematize and communicate evaluation strategies and tools to local and national audiences. As part of the project, teachers participated in action research focused on collaborative investigation of the relationship between formative assessment and student achievement. Early on, we were politely told that art cannot be evaluated and, much less, that children's artwork should not be evaluated. Doing so can threaten children's self-esteem and reduce their motivation to participate in art classes. Recognizing the lack of distinction between assessment and evaluation in this argument, we present theory and research on the differences between summative and formative assessment, or assessment of learning versus assessment of learning (Stiggins 2006), and argue that continuous, informal feedback is Emphasis is placed on how it is done. Both peer and self-assessment have been shown to help students recognize what they value in their learning and performance and identify gaps and opportunities for remediation (Andrade 2010; Topping 2013). By giving, receiving, and resolving feedback, students realize their potential to make valuable contributions to their ensemble. Praise had to come first to help students recognize and build on their strengths and to safely share the improvements they had always expressed as desired. When the focus was on expressive movements or vocal tasks that were difficult to assess numerically (e.g., pretending to walk through a room where supergravity or zero gravity existed), children were asked to observe each other. Describe and explain who did something notable. Students who lacked the verbal skills necessary to describe what they saw were invited to imitate it instead. This course served as an introduction to some elements of vocal and physical expression, as well as narrative peer assessment. Self-assessment via videotape. Self-assessment of storytelling was introduced late in the rehearsal process. Each child chose a story to tell to the rest of the class. They had time to practice their presentations, receive peer feedback, and make revisions. Children also viewed a rehearsal videotape and selected one or more improvement goals from a checklist. Video recording rehearsals has proven to be a powerful tool in helping students improve their playing and technique. Being able to see their progress through video had a huge impact on the children's confidence and performance. Some children were embarrassed to see a video of themselves, but most were very happy and proud. Conclusion In a meta-analysis of recent studies on learning, Hattie (2009) concluded that the greatest effect on her students' learning occurs when her teacher becomes a learner of her own teaching, and when the students become their own teachers. Demonstrates desirable attributes in a learner, including self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-teaching. One of the successes of the Artful Learning Communities project is that it has improved motivation, engagement and learning in art-making by helping students learn how to learn from themselves and each other through self-assessment and peer assessment. Another success of this project was that it helped teachers learn about the role of formative assessment in their own teaching. Classroom observations and conversations with teachers and students revealed that revisions and improvements became more natural, in part because the feedback students received was based on clearly articulated standards they understood and owned. Slow like a Snail!Grandma Moses (1860-1961), known as America's national painter, began her painting at the age of 75. She first picked up a brush and started painting at an age when most people would have thought it was the end of her life, and she left behind many works that are loved not only in the United States but also around the world. She never studied art at school. However, by the time she passed away at the age of 101, she had left behind 1,600 of her paintings to the world. She said that 250 of her paintings were done after she was 100 years old, which shows that there is no limit to the age at which she can paint. She said, “How fortunate she is that she can now draw. In my case, the new life I chose after turning 70 enriched my life for the next 30 years. “ Edward Hopper also began publishing his works after the age of 40. Hopper, who graduated from art school and worked as an illustrator, drew his famous work ‘Night Hawk’ when he was 60, and ‘Room by the Sea’ when he was 70. Henri Rousseau was also born into a poor family, was unable to attend art school, and had to become a customs officer to make a living. He worked as a Sunday painter and drew pictures in his spare time. Because of his amateurish beginnings, the art world ridiculed him for his speaking style and career. But later he perfected his own style and became a master. As an artist, if you look around you you will see people who want to draw but are hesitant to start. I always tell them that they have these amazing mentors. Anyone can draw with just a pencil. Since you are the one who creates your limits, all you have to do is break through your own mold. Yesterday, 11-year-old Sophia used a tablet for the first time to create a digital image in Photoshop. I really like students’ interests and attempts. This is because I know very well how these attempts come together every day and produce amazing results in the future. If we can continue our interests early instead of starting late, the results will be even more amazing.

I think the job of a teacher is to continuously stoke this interest so that it does not perish. I hope her future shines like a sparkling talent. |

Myungja Anna KohArtist Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed