A note: Formative Assessment in Theatre Education: An Application to Practiceby Chen, F., Andrade, H., Hefferen, J., & Palma, M. Arts educators tend to have two opinions on evaluation: Either they believe, often correctly, that they are continually evaluating student learning as a natural part of their practice, or they believe that the important outcomes of their teaching defy systematic assessment (Colwell 2004). Some educators argue that rubrics can actually ‘hurt kids,’ replace professional decision making by attempting to standardize creative processes (Wilson 2006), and undermine learning by focusing only on the most quantifiable and least important qualities of student work (Kohn, 2006). In fact, research on writing has shown that rubrics that emphasize qualities of writing typically considered to be highly subjective and difficult to teach, such as ideas and voice, are associated with meaningful improvements in students’ handling of those qualities in their writing (Andrade, Du and Mycek 2010; Andrade, Du and Wang 2008). Student participation in the assessment process, with or without a rubric, is a key component of assessment for learning (Stiggins 2006), or formative assessment.

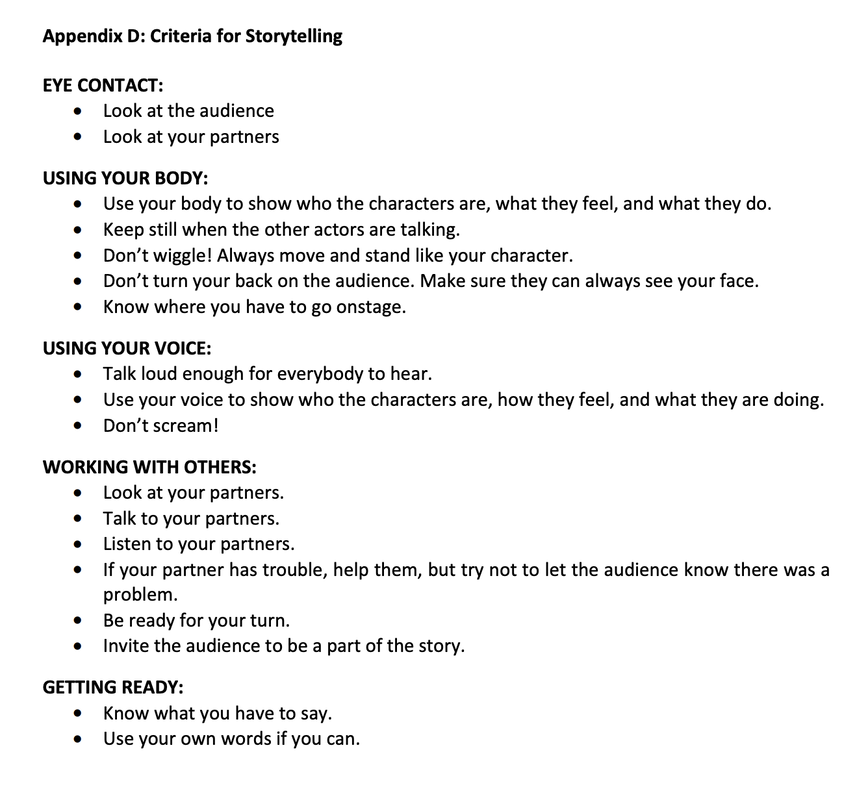

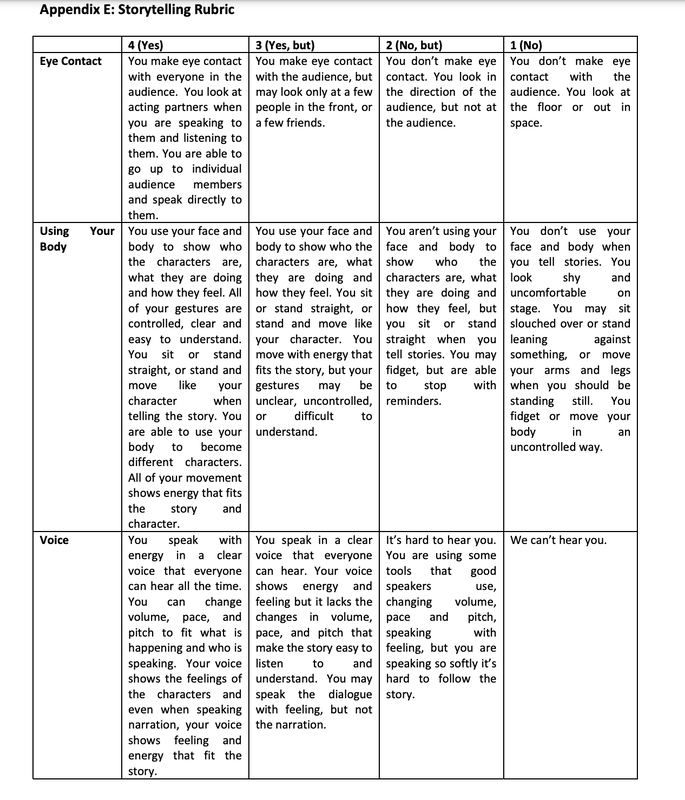

A key element of formative assessment is feedback to teachers and students, both formal and informal, about how much and how well students have learned. Research has shown that well-implemented formative assessment can effectively double a student's rate of learning (Wiliam 2007/2008).The heart of theater is the rehearsal process, where actors receive feedback on their performances and It is a continuous, formative assessment experience where you revise accordingly. Our work with theater professionals participating in a project called Artful Learning Communities: Assessing Arts Learning (ALC) strongly suggests that the results of formative assessments in theater education are similar to those reported in the studies cited above. The goals of the project are to: 1) Strengthen the capacity of elementary and middle school arts professionals to assess standards-based learning in the arts; 2) Promote improved student arts achievement through ongoing classroom assessment. 3) Develop the capacity of professionals to define, systematize and communicate evaluation strategies and tools to local and national audiences. As part of the project, teachers participated in action research focused on collaborative investigation of the relationship between formative assessment and student achievement. Early on, we were politely told that art cannot be evaluated and, much less, that children's artwork should not be evaluated. Doing so can threaten children's self-esteem and reduce their motivation to participate in art classes. Recognizing the lack of distinction between assessment and evaluation in this argument, we present theory and research on the differences between summative and formative assessment, or assessment of learning versus assessment of learning (Stiggins 2006), and argue that continuous, informal feedback is Emphasis is placed on how it is done. Both peer and self-assessment have been shown to help students recognize what they value in their learning and performance and identify gaps and opportunities for remediation (Andrade 2010; Topping 2013). By giving, receiving, and resolving feedback, students realize their potential to make valuable contributions to their ensemble. Praise had to come first to help students recognize and build on their strengths and to safely share the improvements they had always expressed as desired. When the focus was on expressive movements or vocal tasks that were difficult to assess numerically (e.g., pretending to walk through a room where supergravity or zero gravity existed), children were asked to observe each other. Describe and explain who did something notable. Students who lacked the verbal skills necessary to describe what they saw were invited to imitate it instead. This course served as an introduction to some elements of vocal and physical expression, as well as narrative peer assessment. Self-assessment via videotape. Self-assessment of storytelling was introduced late in the rehearsal process. Each child chose a story to tell to the rest of the class. They had time to practice their presentations, receive peer feedback, and make revisions. Children also viewed a rehearsal videotape and selected one or more improvement goals from a checklist. Video recording rehearsals has proven to be a powerful tool in helping students improve their playing and technique. Being able to see their progress through video had a huge impact on the children's confidence and performance. Some children were embarrassed to see a video of themselves, but most were very happy and proud. Conclusion In a meta-analysis of recent studies on learning, Hattie (2009) concluded that the greatest effect on her students' learning occurs when her teacher becomes a learner of her own teaching, and when the students become their own teachers. Demonstrates desirable attributes in a learner, including self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and self-teaching. One of the successes of the Artful Learning Communities project is that it has improved motivation, engagement and learning in art-making by helping students learn how to learn from themselves and each other through self-assessment and peer assessment. Another success of this project was that it helped teachers learn about the role of formative assessment in their own teaching. Classroom observations and conversations with teachers and students revealed that revisions and improvements became more natural, in part because the feedback students received was based on clearly articulated standards they understood and owned.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Myungja Anna KohArtist Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed